The Art of Co-Parenting

- Crystin Rice

- Jun 19, 2024

- 10 min read

Updated: Jul 20, 2024

Artists bring their own unique style and flair to a project, and co-parenting calls us to create something uniquely ours as well - something that fits our family, our values, our kids' personalities, and our situation.

I recently had the honor of joining podcast host Latashia Renee and life coach Jovanna Surillo to talk about some tools that people can use when crafting their own co-parenting arrangement.

The Canvas: Boundaries

Every canvas has an edge, the boundary where the it ends. It is the way of defining where the art is...and where it is not. Our boundaries work the same way - defining what is us, what is in our control, and what is not.

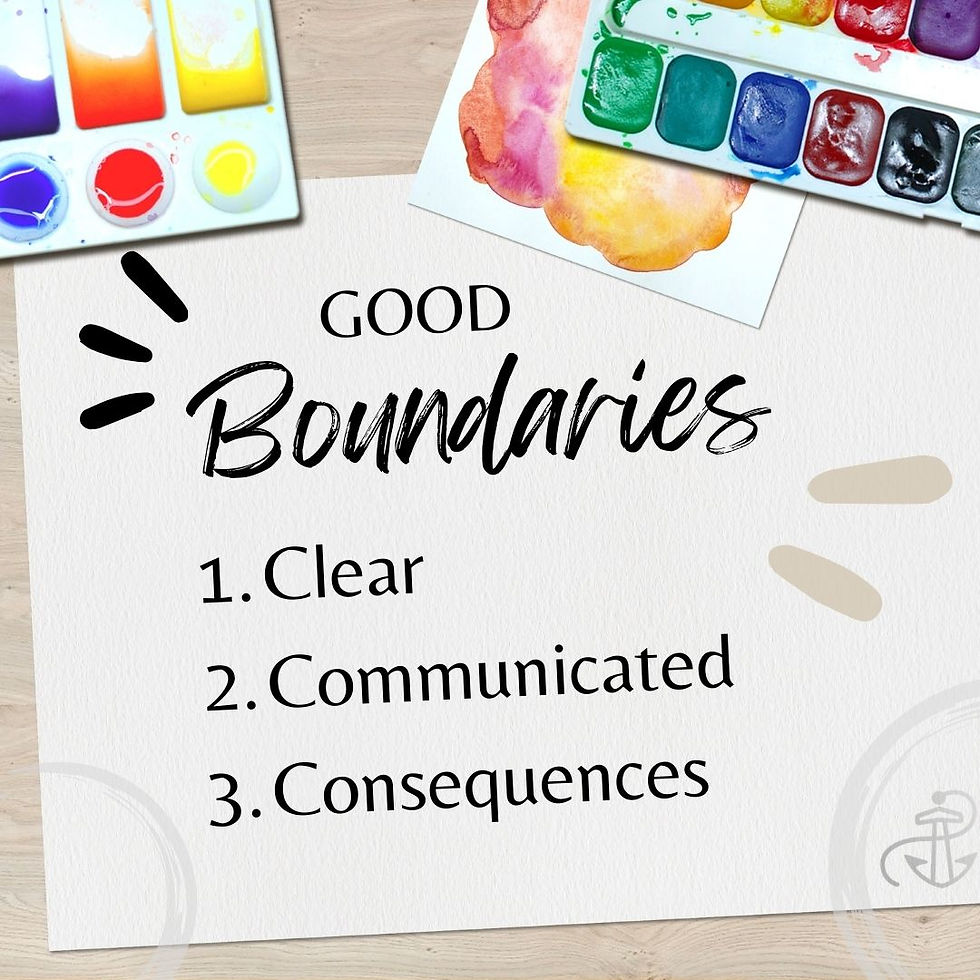

All good boundaries involve the three Cs:

You are clear on (1) what your boundary is AND (2) what the consequence will be if the boundary is crossed. This means you know what you will and won't tolerate, and you also know what you will do about it. You can only control yourself, so a consequence is always about what you will you do, not what you want others to do. (Ex. If you continue to text me during the night, I will have to silence all texts from your number and will only communicate by email until I can trust you again.)

You communicate that to the other parent. Make it clear what your expectations are and what you will do if boundaries are crossed. This helps the other parent know how to be successful with you.

You consistently enforce the consequence. Boundaries that aren't enforced might as well not exist.

Boundaries that can be helpful to outline in co-parenting include:

How you each will commit to keeping the child out of the middle of your conflict.

How much access the child's other parent has to you.

What you do and don't share with your child.

When, where, and how you will have discussions that should not involve the child (tip: not at pickup/dropoff).

Agreements about how and when to introduce new people into the child's life, such as new partners.

How much say a partner has in what happens when the child is with the other parent.

How decisions about medical care, education, extracurricular activities, and the child's expenses are made.

The most important boundary in co-parenting is to keep the kids out of the middle and away from the adult conflict. Family research has repeatedly shown that one of the most harmful conditions for children is exposure to or involvement in their parents’ conflict. Ways you can keep your kids away from damaging messages and conflict include:

Find ways to relay messages to the other parent that do not involve your child (e.g. do not ask the child to deliver verbal or written messages and do not put notes for the other parent in the child's belongings). Children can end up feeling worried about the other parent’s response and stressed because they may feel the parent's emotional reaction is their fault because they are the one who brought the message to them.

Do not "speak through" the child or use the child as a weapon against the other parent by saying the child is requesting something that is actually a request from you.

Do not indicate that one parent is "good" or "bad." Don’t badmouth or put down the other parent in front of the children. It makes them feel torn and bad about themselves because they love the other parent.

Try to maintain a working business relationship in front of your child. It is best to not ignore the other parent or sit on opposite sides of the room during school or sports activities, making the child feel torn about where to go first or how to share equal attention with you both.

Do not use your child as your confidant, and also do not unload your feelings on family members who will continue to have interactions with the other partner because that poisons those relationships. Vent your feelings only to a trusted friend or two who won’t spread gossip. Or save it for a therapist.

Make it easy for your child to love the other parent. Love your child more than you dislike the other parent.

Trying to win the kids to your side can have the opposite effect. Do not share texts or messages from the other parent with your child to “prove” your position or innocence. If the child has a question, they can ask the other parent.

Don’t ask kids to spy. Kids may be good observers but they are unreliable interpreters. Speak for yourself and get information for yourself.

Save talk about the divorce or other grown‐up stuff for times when your child is not present. It can be tempting to discuss concerns during the transition between homes because you are both there, but make a commitment that you will save these conversations for other times. The transition time is about helping the child move between homes.

Do not keep the child from visits or prevent them from texting/talking to the other parent on the phone when you are having a disagreement. Keep the disagreement between the adults and do not use the child as an object.

If the other parent is inconsistent or breaks promises to the child, focus on helping the child, instead of trying to control the other parent. You do not need to make excuses for the other parent or feel a need to “make it up” to the child because that sets the expectation that you will always step in and make life fair for them instead of helping them learn to cope with disappointment. When the child grows up, they will be able to manage difficulty on their own instead of always looking to others to solve their problems.

Also do not make comments about the other parent’s character, such as “This is who they are, this is what they always do, you can never count on them.” Simply let the child share with you what they are feeling and offer compassion and support about the disappointment and hurt they may be feeling. Then ask them how they might handle their feelings, just as you would if they came home hurt by a friend at school, and offer assistance as needed.

The Paintbrush: Your Tools for Communicating

When entering into co-parenting, you move from the intimate relationship you once had with each other to a business partnership focused on the task of raising children. This means washing your paintbrush from the colors you used to paint with and starting fresh.

Why is that important?

As Isolina Ricci, PhD explains in her book Mom's House Dad's House, there are three basic kinds of relationships, which are defined by the types of rules and expectations that are involved.

Business/Acquaintance

Formal courtesies

Well-defined agreements and contracts

Low emotional intimacy and investment

Take place in public spaces

Friendship

Increased personal disclosure and trust

More automatic reciprocity, forgiveness, and support

Increase in private settings

Intimacy

Significant amount of personal information is known

High intensity of emotions

Greater amount of assumptions about the roles in relationship and expectations

Informal

Intimacy is further divided into positive intimacy and negative intimacy.

In positive intimacy, confidences are protected and there is a great deal of forgiveness and acceptance of the whole person. The relationship is marked by trust, security, and comfort. Reciprocity and cooperation are assumed.

In negative intimacy, the benefits of positive intimacy have eroded and resulted in feelings of rejection, lack of safety, distrust, and competition. Assumptions and expectations are generally negative.

Parents generally have progressed to the stage of intimacy in their relationship before separating, and it likely has devolved into negative intimacy.

Successful co-parents start over with a new canvas. They go back to a business relationship where they follow formal courtesies, create written contracts for expectations and responsibilities, and stay focused on the business at hand (parenting the children). It takes time and effort to develop this new kind of relationship with new rules and expectations, but it can also save time and stress spent dealing with the pain of negative intimacy.

The Palette: A Place for All the Emotions

When you are starting a co-parenting situation, it probably means you are also grieving a dream. You had an idea of what your future looked like as a parent, and for whatever reason, that didn't happen. Now you're grieving the dream of what you had envisioned. The other person is also grieving a dream, and very often the two of you aren't in the same place in your grief. Usually one partner had a head start, (often the one who made the decision to end the relationship).

So you've got two people navigating the emotions of denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance all at different times as well as the many other emotions that come with moving into this new task of co-parenting. It gets messy.

Add to that the research that Katherine Woodward Thomas discusses in her book Conscious Uncoupling that says love withdrawal mirrors drug withdrawal in the brain. We are wired to keep seeking what activates that circuit, so we engage in patterns that activate it even though they are hurting us. That can often be why we feel compelled to keep reaching out to the child's other parent, even if it's just going to start a fight. We bond biologically and psychologically in ways that make us deeply reliant on those we are close to, and Thomas says ending that relationship can be as traumatic as the severing of a limb.

In the midst of the swirling chaos of all these emotions, you have to figure out how to make decisions together and work together. It's likely you have already created some patterns of not doing that very well, so be compassionate toward yourself as you work through undoing the old and creating something entirely new.

The Paint Colors: What Your Co-Parent Relationship Looks Like

How to make decisions

Decision-making in the early days of creating a co-parenting relationship can be overwhelming. If you are also in the process of a divorce, you are likely reeling from decision overload - making all the decisions about how to split finances & property, where to live, your new budget, etc. Add to that the decisions about how much time kids spend with whom, how to manage holidays and special occasions, how to split financial decisions about the kids, etc. and you may find that deciding what's for dinner can put you over the edge!

It can be time-consuming and burdensome to try to negotiate every parenting decision individually, and without a plan in place about decision-making processes, parents may resort to arguing or asking the court to make their decisions for them. Arguing makes it difficult on everyone. Asking the court to make default decisions gets expensive, and it's ultimately frustrating because the court can only offer rigid templates that don't allow for the everyday circumstances that require more flexibility. Consider developing a default decision-making approach. Default decision-making isn't unique to co-parenting; even married couples often use this approach.

The default system does not settle their disagreement, but it settles the question of who will make the decision if consensus cannot be reached. The primary ways couples do this fall into two main approaches.

Parallel Parenting

In parallel parenting, each parent has the authority to make parenting decisions when it is their time with the children, and these decisions may be different from the rules at the other parent’s home. This is often the recommended arrangement for high-conflict situations. Conflict is reduced by respecting the autonomy of each parent to make their own decisions on their own time and in their own homes.

Activity-Specific Authority

Another way to structure decision-making is for each parent to have the default authority to make decisions in different aspects of their children’s lives, especially when the parents frequently disagree on a particular topic. In this type of structure, both parents agree to uphold the decisions of the other parent whenever the children are involved in the activity that the other parent has authority over. It does not matter whose house the children are in or which parent is currently on duty. What matters is what activity children are involved in.

Examples include:

One parent has decision-making say over sports and the other handles academic choices.

One parent sets bedtime and curfew rules and the other manages health care practices and doctor visits.

When one parent is more concerned than the other about a child’s success in learning a musical instrument, for example, it may make most sense for that parent to have default authority over the choice of instrument, teacher, practice schedule, etc. The parent with default authority earns this privilege not only through their concern or passion about the activity, but also through their willingness to do most of the work of actively helping the child in the activity.

Remember that the goal is to do what's best for the children.

Although it's helpful to have a default decision strategy, it's also important that both parents are involved in some part of the decision-making. When one parent is the default decision-maker in all areas, the other parent may fade away from involvement or resist the arrangement with either open conflict or passive aggressive chaos. This is because a parent who doesn't have the sense that they are important personally to their children may find it easier to drop out of their children’s lives completely. Or they may not directly oppose the authority parent on any issue, but may use passive-aggressive tactics such as “forgetting” to comply, or half-way comply, or “misinterpreting” instructions. In this way the non-authority parent creates some opportunity to have autonomy without appearing to oppose the authority parent. These dynamics are the predictable results of a failure to negotiate a workable default decision-making system.

Further, once you negotiate a workable system, remember that nothing is set in stone.

Children’s lives keep changing as they grow, so you must regularly renegotiate in order to make sure the system is most appropriate for the children's needs.

When you don't agree on parenting style

It's helpful when both parents have the same rules in the home. Children whose parents can come to agreement on this will benefit from the consistency and stability that provides. If this seems out of reach, though, don't despair. Even married couples rarely have the same ideas about bedtime, chores, and how children spend their time. It's not necessarily realistic to think that you and the other parent will come to 100% agreement on this. Instead, focus on how to help the child transition between homes where the rules are not always the same.

The Message: What does your co-parenting communicate?

Every great piece of art communicates something. The way you develop your co-parenting expresses more than just expectations and rules to your child. Your children are always watching to see how you navigate conflict as well as how you manage and express your emotions. The example you set will likely become their strategy for dealing with conflict as they go out into the world. Artists rarely just start painting and see what happens; instead, they usually have some idea of what the final product will look like. Consider what you want your children to learn about working through hard tasks, and begin with the end in mind.

If you find that you are having a hard time crafting the message you want your children to see, consider reaching out to a therapist to assist you with having productive discussions with the other parent, sketching out helpful boundaries, and keeping your child's best interest as the focal point.

Comments